One hundred years after the death of Emily Davison at the 1913 Derby, we look at the way leading suffragettes sought to galvanise support for their cause.

“We were called militant, and we were quite willing to accept the name. We were determined to press this question of the enfranchisement of women to the point where we were no longer to be ignored by the politicians.” Emmeline Pankhurst, 1913.

We recently ran an article examining the influence styles and techniques used in 10 famous speeches, showing how speakers attract an audience to their way of thinking by emphasising common ground, by sharing visions of a united future, by proposing, reasoning and persuading, and by maximising their impact through rhetorical devices such as three-part lists and contrasting pairs.

Now, following the centenary of the most shocking occurrence in the history of the suffragette movement – the death of activist Emily Davison after she stepped in front of King George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913 – we look at the speeches, writings and street corner oratory from leading suffragettes and women’s rights campaigners in Britain and America.

The late Victorian roots of the campaign for universal suffrage in Britain saw the growth of non-militant groups known as suffragists, who held meetings and sent petitions to Parliament. In 1897 they amalgamated into the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, led by Millicent Fawcett, before Emmeline Pankhurst started the Women’s Social and Political Union with the motto ‘Deeds not words’ in 1903. Historians still debate whether the militant tactics ultimately helped or hindered the cause, but the influence of their words can still be felt a century later.

Emmeline Pankhurst, ‘Freedom or death’ speech, 1913

Emmeline Pankhurst was an activist and leader of the British suffragette movement. Born and raised in Moss Side, Manchester, she was introduced to the concepts of the movement from a very early age by her politically active parents. The excerpts below come from a speech she delivered in Hartford, Connecticut, in November 1913.

“I am not only here as a soldier temporarily absent from the field of battle. I am here—and that, I think, is the strangest part of my coming—I am here as a person who, according to the law courts of my country, it has been decided, is of no value to the community at all. And I am adjudged because of my life to be a dangerous person, under sentence of penal servitude in a convict prison. So you see, there is some special interest in hearing so unusual a person address you. I dare say, in the minds of many of you—you will perhaps forgive me this personal touch—that I do not look either very like a soldier or very like a convict, and yet I am both . . .

“You have two babies very hungry and wanting to be fed. One baby is a patient baby, and waits indefinitely until its mother is ready to feed it. The other baby is an impatient baby and cries lustily, screams and kicks and makes everybody unpleasant until it is fed. Well, we know perfectly well which baby is attended to first. That is the whole history of politics. You have to make more noise than anybody else, you have to make yourself more obtrusive than anybody else, you have to fill all the papers more than anybody else, in fact you have to be there all the time and see that they do not snow you under.

“If you are dealing with an industrial revolution, if you get the men and women of one class rising up against the men and women of another class, you can locate the difficulty; if there is a great industrial strike, you know exactly where the violence is and how the warfare is going to be waged; but in our war against the government you can’t locate it. We wear no mark; we belong to every class; we permeate every class of the community from the highest to the lowest; and so you see in the woman’s civil war the dear men of my country are discovering it is absolutely impossible to deal with it: you cannot locate it, and you cannot stop it.

“‘Put them in prison,’ they said, ‘that will stop it.’ But it didn’t stop it at all: instead of the women giving it up, more women did it, and more and more and more women did it until there were 300 women at a time, who had not broken a single law, only ‘made a nuisance of themselves’ as the politicians say.”

Millicent Fawcett, Electoral Disabilities of Women, 1872

In 1866, aged just 19, Millicent Fawcett became secretary of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. She would eventually become leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1890, a post she held until after women were granted the vote in 1918. When setting our her arguments, her approach and tone is more moderate than the Pankhursts, but equally determined. ‘Electoral Disabilities of Women’ appeared in Essays and Lectures on Social and Political Subjects, written with her husband Henry.

“In Turkey, a woman who walked out with her face uncovered, would be considered to have lost all sense of propriety — her conduct would be highly repugnant to the feelings of the community. In China, a woman who refused to pinch her feet to about a quarter of their natural size, would be looked upon as entirely destitute of female refinement. We censure these customs as ignorant, and the feelings on which they are based as quite devoid of the sanction of reason. It is therefore clear that it is not enough, in order to prove the undesirability of the enfranchisement of women, to say that it is repugnant to the feelings. It must be further inquired to what feelings women’s suffrage is repugnant, and whether these feelings are ‘necessary and eternal’, or ‘being the results of custom, they are changeable and evanescent’. I think these feelings may be shown to belong to the latter class.”

Christabel Pankhurst, recording, 1908

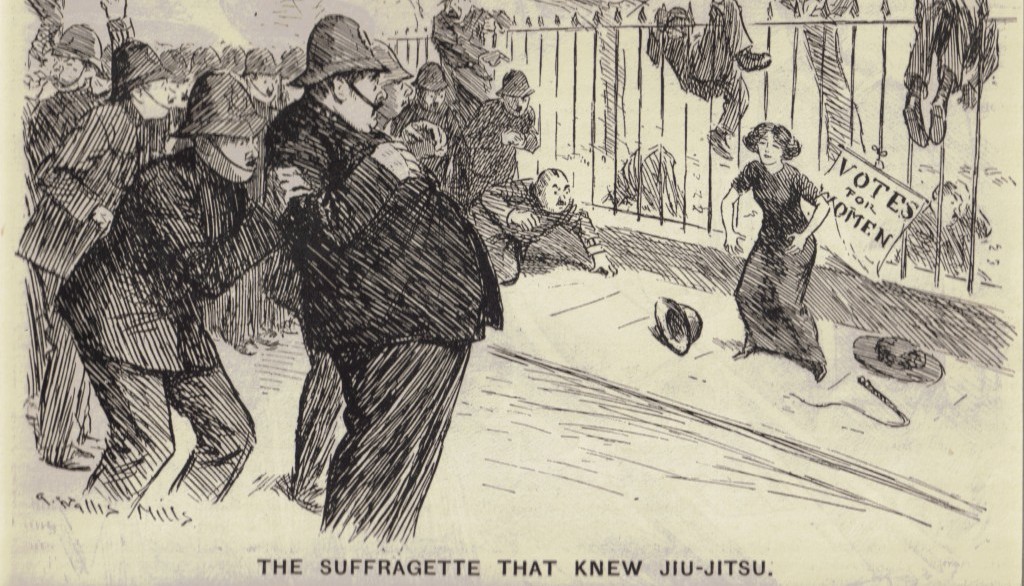

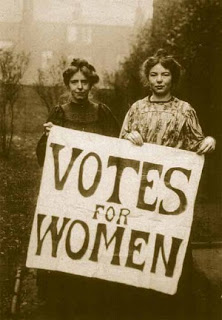

Born in 1880, Christabel Pankhurst was Emmeline’s eldest child. In 1905, after interrupting a Liberal Party meeting with shouted demands for voting rights for women, she and fellow suffragist Annie Kenney (both pictured below) were sent to prison rather than paying a fine. This attracted much attention to the cause and the WSPU itself. This rare recorded speech was made in 1908, just hours after being released from another stint in prison. While the anti-suffrage press presented suffragettes as unstable extremists, the recording reveals a rhetorical style that is measured, reasonable and deliberate. You can listen to the original via the British Library.

“For forty years, this reasonable claim has been laid before Parliament in a quiet and patient manner. Meetings have been held and petitions signed in favour of votes for women but failure has been the result. The reason of this failure is that women have not been able to bring pressure to bear upon the government and government moves only in response to pressure. Men got the vote, not by persuading but by alarming the legislators. Similar vigorous measures must be adopted by women. The excesses of men must be avoided, yet great determination must be shown. The militant methods of the women today are clearly thought out and vigorously pursued. They consist in protesting at public meetings and in marching to the House of Commons in procession. Repressive legislation make protests at public meetings an offence but imprisonment will not deter women from asking to vote. Deputations to parliament involve arrest and imprisonment yet more deputations will go to the House of Commons . . .

“They must be compelled by a united and determined women’s movement to do justice in this measure . . . we have waited too long for political justice; we refuse to wait any longer. The present government is approaching the end of its career. Therefore, time presses if women are to vote before the next general election. We are resolved that 1909 must and shall be the political enfranchisement of British women.”

Susan B. Anthony, pre-trial address, 1873

Susan Brownell Anthony played a pivotal role in the suffrage and women’s rights movements in America. She was co-founder of the Women’s Temperance Movement and women’s rights journal The Revolution. In November 1872, she was arrested for voting in the Presidential Election, and this address was delivered prior to the subsequent trial in June 1873.

“The preamble of the federal constitution says: ‘We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and established this constitution for the United States of America.’

“It was we, the people, not we, the white male citizens, nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed this Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings or liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men. And it is downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government — the ballot.”

Sylvia Pankhurst, preface, 1911

Sylvia Pankhurst worked full-time with the Women’s Social and Political Union from 1906. Later, unlike both her sister and mother, she would not not support the war effort, and became both a prominent pacifist and socialist. The excerpt below comes from the preface to her 1911 history of the women’s militant suffrage movement.

“To many of our contemporaries perhaps the most remarkable feature of the militant movement has been the flinging-aside by thousands of women of the conventional standards that hedge us so closely round in these days for a right that large numbers of men who possess it scarcely value. Of course it was more difficult for the earlier militants to break through the conventionalities than for those who followed, but, as one of those associated with the movement from its inception, I believe that the effort was greater for those who first came forward to stand by the originators than for the little group by whom the first blows were struck. I believe this because I know that the original militants were already in close association with the truth that not only were the deeds of the old time pioneers and martyrs glorious, but that their work still lacks completion, and that it behoves those of us who have grasped an idea for human betterment to endure, if need be, social ostracism, violence, and hardship of all kinds, in order to establish it. Moreover, whilst the originators of the militant tactics let fly their bolt, as it were, from the clear sky, their early associates rallied to their aid in the teeth of all the fierce and bitter opposition that had been raised.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments, 1848

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was both an abolitionist and leading figure of the women’s rights movement in America. These are the closing remarks from her influential ‘Declaration of Sentiments’, which was presented at the first women’s rights convention held in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York.

“Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation—in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States. In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.”

Emmeline Pankhurst, letter, 1913

This letter was written by Emmeline Pankhurst to members of WSPU on 10th January 1913, outlining the case for militancy. You can view a copy of the original via The National Archives.

“There are degrees of militancy. Some women are able to go further than others in militant action and each woman is the judge of her own duty so far as that is concerned. To be militant in some way or other is, however, a moral obligation. It is a duty which every woman will owe to her own conscience and self-respect, to other women who are less fortunate than she is herself, and to all those who are to come after her.”

Annie Kenney, speech, 1908

Annie Kenney rose to notoriety in 1905, when she was imprisoned with Christabel Pankhurst after heckling a Liberal rally. Unlike many other leading lights of the movement, she came from a poor working class background. She began her working life in a cotton mill at the age of 10. Despite having one of her fingers ripped off by the machinery, she remained at the mill, becoming involved in trade-union activities and leading an educational drive for fellow employees. She gave this speech at a suffrage meeting held at the Royal Albert Hall in March 1908.

“Let us just look at the conditions the people of our land are living under today. Just think, and then be satisfied with life as it is if you can! Your prisons are full, your workhouses are overcrowded, your lunatic asylums are overcrowded. You have over thirteen million starving women, men and children. You have your thousands of underpaid, sweated women workers, and we want to consider what all this means to we women! Have you ever been in our British institutions? Have you been in your workhouses and seen your old women packed together, just at the time of life when they should be made bright and comfortable for their old age, to give those tired hands and weary hearts a chance of rest? Have you ever been in our maternity wards? And seen our young girl mothers? Have you ever been in our imbecile wards, and seen the children that are born of women, some of the children that are born in sin? It would be wrong if the women were satisfied; it would be wrong if we women did not burn with righteous indignation. Where is our religion, where is our Christianity, if we are prepared to stand by without lifting our hands to help?”

Mary Humphrey Ward, The Times, 1909

To end on a counterpoint, and to illustrate what the suffragettes were up against, here’s a short excerpt from author Mary Humphry Ward, who was approached by Conservative leader Lord Curzon and Labour politician William Cremer to become the first president of the Anti-Suffrage League.

“Women’s suffrage is a more dangerous leap in the dark than it was in the 1860s because of the vast growth of the Empire, the immense increase of England’s imperial responsibilities, and therewith the increased complexity and risk of the problems which lie before our statesmen – constitutional, legal, financial, military, international problems – problems of men, only to be solved by the labour and special knowledge of men, and where the men who bear the burden ought to be left unhampered by the political inexperience of women.”

Recent Comments