‘I gave him his head . . .’ A tale of strong but sympathetic leadership in a crisis

You have a star performer. He has a wide skillset, shows dogged perseverance, great accuracy and determination. Not only that, he’s a galvanising member of the team – he’s relaxed, charming, with a boyish sense of humour, and yet has the steely resolve of a born competitor, inspiring – and drawing inspiration from – those around him.

His performances attract more and more attention. This leads to a rapid promotion – too rapid. As team leader, his performances dip, his goals are no longer achieved, his confidence nosedives, and he’s suddenly, seemingly, yesterday’s man.

He steps down. He finds himself back in the same old surroundings – just another member of a team. Not only that, but a team in crisis.

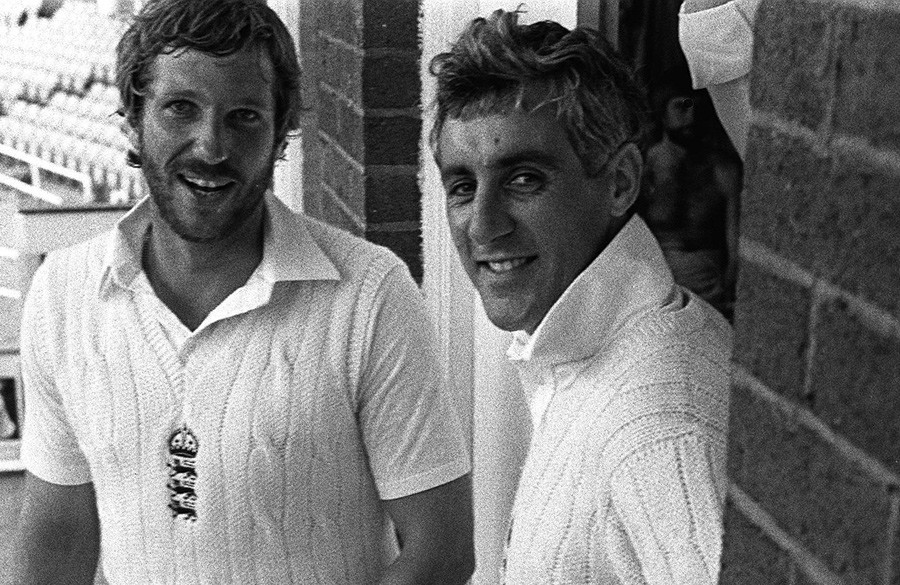

Luckily, his nickname is Beefy and his new team leader is Mike Brearley.

It’s tea on the fourth day of the third test. England’s cricketers are already one-nil down in the 1981 Ashes Test series against Australia. The scoreboard at Headingley displays the latest odds from Ladbrokes.

1-4 – Australian win

5-2 – Draw

500-1 – England win

Australia made 401 runs in the first innings. Having dismissed England for 174, they enforced the follow-on, making England bat again.

Writing in The Cricketer, Christopher Martin-Jenkins said: “Ian Botham, magically transformed in his first match away from a captaincy which had weighed more heavily than Frodo’s ring, stole the Third Test from Australia in two hours of thunderous driving. Coming in at 105 for 5, with England still 122 behind, his brilliance, bravado and, in [Australian captain] Kim Hughes’s words, his ‘brute strength’, gave England’s bowlers 129 runs to play with. At 56 for one their cause seemed hopeless but Bob Willis took eight of the last nine wickets, Mike Gatting and Graham Dilley held crucial catches and the daylight robbery was completed amidst national rejoicing.

“Only once before had a Test been won by a side following on [in 1894] . . . But the speed with which the match at Headingley was turned upside down made it unique; something one expects to witness only once in a lifetime.”

How was it done?

A huge number of factors, including blind luck, played into that most decisive rediscovery of form. What would become England’s most famous cricketing victory, wasn’t just down to Botham. His astounding innings opened the door, but it was Bob Willis’ decisive bowling spell that snuffed out the Australian run chase.

Part of the credit for Botham’s turnaround must go to the influence of his Captain Mike Brearley. Brearley’s leadership loosened the shackles.

So what was his leadership style? How had he produced such a transformation in the man who had been going through such a poor run of form – including a pair of ducks at the Lord’s test?

The team selectors, in their wisdom, had put Botham in charge on a match by match basis, ramping up the pressure and clearly affecting his confidence, leading to his resignation after the second test.

Speaking to reporters at the time, Botham said: “Basically I feel that it’s unfair to myself and the team to continue on a one-match basis because . . . I don’t know what’s happening and the team doesn’t know what’s happening and I think that it will be better for all concerned if someone else comes in and hopefully gets the job for the remaining tests.”

Brearley was an old school tie character, by no means an outstanding player, who had retired from the captaincy the previous year to train as a psychotherapist.

In a 1996 BBC documentary about the 1981 Ashes Series, Australian bowler Dennis Lillee said: “I didn’t rate him as a player at all. From that point of view I was happy to be bowling to him.”

Brearley’s greatest attribute was the ability to listen, to understand his players’ motivations and to coax the best out of them through strong, yet understanding leadership. Through listening and involving his team, he brought them together and ignited a string of outstanding performances from the dangerous and talismanic Ian Botham.

Geoff Boycott explains: “[Brearley] tries to understand people pretty well and that’s his strong point. It certainly isn’t his batting.”

Cricket writer Chis Lander, who covered the series for the Daily Mirror, said: “Brearley knew how to handle him [Botham]. How to talk to him. How to get the best out of him. How to make him respond. He was able to talk to him in a sort of fatherly way. And many other people probably couldn’t in cricket at that time.”

Botham himself, in the foreword to Brearley’s book about the 1981 series, wrote: “There is something about Brears. He knows how I feel and what I’m thinking . . . I took stuff from him that I’d clip other guys round the ear for.”

Psychotherapist Edward Marriott’s online article ‘Freud in the slips’ noted how Brearley’s reinvigoration of Botham used a combination of carrot and stick.

“Before the match Brearley said that Botham would score a century and take 12 wickets; then, when Botham was bowling hesitantly, Brearley withdrew him from the attack and dubbed him the ‘sidestep queen’ to goad him into action. Then, when Botham went in to bat, Brearley told him to ‘go for it, enjoy yourself.’”

According to Brearley, writing for the Guardian on the 30th anniversary of the match in 2011: “I had been Botham’s first Test captain, I knew him well; he and I got on well, if at times turbulently. He was excellent for me and not only in the obvious ways – taking wickets, scoring hundreds, and catching brilliantly at second slip. He also made me feel younger, made me laugh, kept me on my toes. He would tease me, bring me down to earth, so there was something symmetrical in our interaction, as well as the more obvious asymmetry . . . But at least he was getting loose . . . So I was able to make some early assessments of him at Headingley, and Botham responded. I got him to run in faster to bowl . . . When he batted, I reckoned he was better off on that dodgy Headingley pitch in hitter mode than trying to ape his batting betters; I gave him his head.”

Cricket historians and students of the game have called Brearley’s reputation into question. Even during his career as Captain, which ended with a record 58.06% success rate in his 31 Tests between 1977 and 1981, his tactics often came in for criticism. In the days leading up to the 3rd test, Brearley himself even considered dropping Botham and Willis.

But former chairman of selectors Alec Bedser, when asked to pick the best England captain, chose Brearley.

“ . . . the quiet persuader, who twice took over and triumphed when anything less than strong but sympathetic leadership could have led to disaster.”

The signature behaviour of an assertive yet sympathetic leader is active listening. It is through listening and understanding that a leader is able to learn the inner workings of a team, recognise potential challenges, and empower staff to rally around mutual goals. Active listening increases a leader’s influence – the process of listening to others invites others to listen to you. It solicits detailed information, increases group understanding of a project, builds rapport, and helps others feel understood and valued.

Brearley retired for a second time at the end of the 1981 season, having steered the national team to a 3-1 Ashes series win.

Recent Comments